I had also studied conversational German at MIT (see Frau Pan and other entries), although my knowledge of German has slowly declined with disuse. With languages, it's "Use it, or lose it". As I pointed out in my blog entry Le Cercle Français, "The United States has a disadvantage compared with most other countries: pretty much everyone around us speaks the same language. I know that this is in many ways an advantage, but from the point of view of language study, it's not. It's one reason why US citizens are so poor at foreign languages. People learn what is useful to them, and for the everyday living of most Americans, foreign language study is not worth the effort."

"Finally," I thought, "there's a second language that can actually be used (and hence more easily maintained) inside the United States." The only problem: I didn't speak it. Well, that could be easily remedied. I purchased the Living Language Spanish course, which came in a box 26.7 wide by 28.5 cm high (10.5 X 11.25 inches), seen above. It contained two audiotape cassettes, and two paperback books, one of which is shown to the right. Note 1 The course began by introducing the Spanish alphabet, and the language's spelling and pronunciation rules. Spanish spelling is extremely regular, I think due to a relatively recent spelling reform. If you see a word spelled in Spanish, you know how to pronounce it. You even know from the spelling exactly which syllable in the word is stressed, something that can't be said of English or Italian. And if you hear a word in Spanish, you can generally write it down. There are a few exceptions to this: the letter H is silent in Spanish, and there are a number of different letters which can carry the S sound, at least in the Latin American version of the language. The letters B and V are almost impossible to distinguish (see my entry Linguistic Lunacy). But compared with the atrocious spelling/pronunciation correspondence of English, Spanish is a real pleasure.

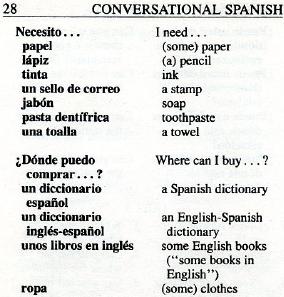

At the top of page 28, shown to the left, I found a list of vocabulary words. The list starts with "necesito" (meaning "I need"), which is followed by a few common things you might find yourself needing to ask for. I learned the words, listened to their pronunciation on the tape, and tried to imitate it. The company I was working for at the time, Kronos Incorporated, used a cleaning crew whose employees I knew to be mostly Spanish-speaking. Working late one evening (not an uncommon occurrence), I found the paper towel dispenser in the men's room to be empty. As I left the room, I noticed a new member of the cleaning crew, a young man, working nearby. I got his attention, and said to him, "We need towels." With gestures, he indicated to me that he was unable to understand me. I immediately thought of my brand new vocabulary, which I had learned only the night before. The list had contained exactly the words I needed. I said to him, "Necesito toallas" (yes, I knew how to make the plural). His face lit up with comprehension, he smiled, and replied, "Sí". I was absolutely delighted. I recall thinking that it was the very first time I had ever truly used a foreign language inside the United States. Precisely the reason I was learning Spanish. Now surely, I had previously spoken French and German to people in the United States. But these were generally people with whom I could have spoken in English if necessary. I was generally taking the occasion to practice my French or German with a native speaker, but native speakers of these languages that I meet within the United States are generally capable of speaking English. But this episode was the first time I had ever, in the United States, used a foreign language to communicate with someone with whom I otherwise would have been unable to communicate had I not spoken that language. That's what I meant by "truly used" in the sentence two paragraphs above. That's why I was learning Spanish, and I was pleased to see that it was working. In late November of 1988, I went on a business trip that took me to Seattle, Washington; Tijuana, Mexico; and finally Los Angeles, California. The purpose of the trip to Tijuana was to inspect the Altos battery factory. This factory was a so-called "maquiladora", a Spanish word for this sort of final assembly facility located just over the border, I think for tax reasons and reduced labor costs. We were considering using Altos as a supplier (I was impressed by their operation, and we did in fact later purchase from them). Approaching customs returning from Tijuana to San Diego, we sat in our car for a while in the long lines at the border crossing. Mexican salesmen walked up and down the lines of cars, attempting to sell the drivers and passengers various Mexican products. I was interested in a Mexican serape, a sort of poncho-like blanket, and I negotiated with the seller in Spanish. Although my Spanish was not very advanced, the negotiations consisted largely of firing numbers back and forth at each other. Thus it was quite easy, as I had learned the words for Spanish numbers very early on. I bargained up and he bargained down, settling on a final price of doce, meaning $12. After crossing the border, a local Kronos sales rep drove us up the California coast from San Diego to the Kronos sales office in Los Angeles. This was again an opportunity to exercise my brand-new Spanish vocabulary. It had never previously dawned on me what the names of all the roads and towns along the California coast meant. As we passed exit after exit, I kept flipping the pages of my dictionary to translate the names from Spanish into English. Of course, probably half of them bore the names of saints, such as San Diego and Santa Clara. To name just a few of the non-saint names: La Presa = the dam El Cajón = the canyon (literally, "the box") Coronado = crowned La Mesa = the mesa (literally, "the table") Escondido = hidden Camino del Mar = road of the sea Mission Viejo = old mission Marina del Rey = marina (or navy) of the king La Puente = the bridge Palos Verdes = green woods Loma Linda = beautiful hill (or ridge) Los Angeles = the angels Note 2 And of course, I thought of other city and town names in California that we didn't pass on this drive: Palo Alto = high wood Sacramento = sacrament and so on Eventually, to continue my study of Spanish, I enrolled in adult education Spanish courses with the nearby Concord Carlisle Adult and Community Education, courses which I've continued to the present day. In general, Spanish is the most useful second language to learn in the United States, and I've gotten a great deal of pleasure and use out of it. Here's a wonderful cartoon about one of the classic difficulties of doing business in Mexico:  In case you don't get it right away: it's a comment on what the word "mañana" could mean, in practice, in Mexico. Although the word literally means "tomorrow", it can actually mean "whenever I get around to it, maybe never". Evidently, the "new guy at the maquiladora" doesn't understand this. You may recall an old song on the subject, "Mañana (is soon enough for me)". Here's a YouTube version by Peggy Lee, from a less politically-correct age. I think these complaints about Mexican workers no longer have much validity in the age of NAFTA.   Note 1: The other book was the Living Language Spanish-English English-Spanish Common Usage Dictionary, an extremely useful volume. One of its benefits is that it highlights the 1,000 most frequently used words in the Spanish language, to help a student learn those words which are most important. It also gives a great many examples showing how words are used idiomatically in everyday conversation. [return to text] Note 2:

It has been said that the full name of Los Angeles is, "La ciudad de nuestra dama, la reina de los ángeles de Porciúncula", meaning "The city of our lady, the queen of the angels of Porciúncula". However, I think there's some controversy about this. Like San Francisco, Los Angeles was founded by Franciscan monks, and Porciúncula was the Spanish name for a small chapel built by Saint Francis in Assisi, Italy. In Italian, the word is Porziuncola, and it's currently located inside the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli, near Assisi. [return to text]

|

The course then proceeded to begin to build vocabulary, starting with words such as numbers and days of the week, and proceeding from there.

The course then proceeded to begin to build vocabulary, starting with words such as numbers and days of the week, and proceeding from there.