The "Le" in the title tells you that "Le stage" is French and not English. Note 1 "Stage" is pronounced to rhyme with "Taj", as in "Taj Mahal". In French, a "stage" is a training course or training period, perhaps best translated as an "internship". In the summer of 1964, I participated in a "stage téchnique", an engineering internship, at the Eléctricité de France ("EDF") in Petit Clamart, near Paris. But a "stage" doesn't have to be technical. For many years, my aunt Barbara, a violinist, taught a "stage de violon" in France each summer. Note 2

I had previously spent a summer in France in the city of Pau in a language study program. Note 3 It was intended to be French immersion, but the other students in the group simply refused to speak only in French. When we were not in our classes, or with our French host families, they always spoke English between themselves. As a result, that program did not turn out to be the full immersion I had hoped for. Although I nevertheless did make substantial progress in my French, I wanted the summer of the stage to be a true immersion experience. That is, I wanted to speak nothing but French during the entire summer. This promised to be quite a bit more difficult for Larry Beckreck than for me, since his only experience in French dated back to high school. Nevertheless, he gamely agreed to go along with my scheme. We switched from English to French at the halfway point in our flight over the Atlantic. I recall Larry commenting on a particularly pretty "luage" we could see through the window. Unfortunately, it turned out later that the French word for "cloud" is "nuage", and not "luage".

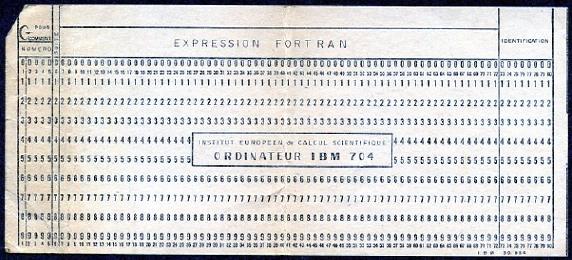

Our boss, Monsieur Pouget, sat us down for an introductory talk, after which he asked us if we had been able to understand him. I replied that I had (more or less), but Larry replied "Pas du tout", which means "not at all". M. Pouget started over, repeating what he had said more slowly and clearly. It later turned out that Larry had intended to say "not completely" which would have been "Pas tout à fait", but he had gotten the two expressions mixed up. Larry and I shared an office at the EDF, where we spent a great deal of time with just the two of us. But we stuck to our plan of speaking only French, even between ourselves. As with the word "luage" that Larry had invented on the airplane, we persisted in periodically inventing nonexistent French words while isolated in our office. I recall one day we came up with the word "savance", which we thought meant "knowledge". As plausible as it sounds (the verb "to know" is "savoir"), it is not a French word, which we found out the first time we used it outside the office. With complete immersion, after a while something in your mind clicks. Your brain seems to conclude, "Uh-oh, English doesn't seem to work anymore, so I'd better pick up this French thing." Suddenly, you start remembering new words after only one exposure. My French started to improve very rapidly, and I also worked a great deal on perfecting my pronunciation. I think Larry's French improved even more quickly than mine, and he actually started dreaming in French. Of course, our conversations with other members of our research group also became easier. We did have a continuing problem understanding a tall, gangly man from Brittany with the uncommon last name Marcilhacy, partly because of his Breton accent, and partly because he always seemed to talk with a Gitane cigarette in the center of his mouth. At some point Monsieur Pouget asked Larry if he had become able to understand everyone. Larry replied in the affirmative, adding "sauf Marcilhacy" ("except Marcilhacy"). Monsieur Pouget thought for a second, and then said, "moi non plus" ("me neither"). Our speaking only French certainly increased our learning speed, but it also had an unexpected side effect: French people were very friendly towards us, and would often strike up conversations on the street. This is not characteristic of the French, who tend to not intrude into the private space of others. But apparently they found it quite unusual to see two Americans speaking French to each other. There were certainly many Americans in Paris that summer who could speak French reasonably well, but when speaking to each other they would generally lapse into English. Yet here were two Americans who would speak to the French in French, and then turn to each other and continue speaking in French. Not only that, but our French was pretty good - we paid attention to noun genders, verb conjugations, and other grammatical points. It was obvious that we were taking the language seriously. I got the feeling that many who struck up conversations were quite curious about us. It was clear we were Americans, since as good as our French might have been getting, we still had distinct American accents. As for our work, Larry and I collaborated on a computer program which (if I'm remembering properly) was used to simulate power distribution network configurations. It was written in Fortran IV for the EDF's IBM 7094 ("ee-bay-em sept mille quatre-vingt-quatorze"). Larry and I had come from MIT, which was already running an advanced time-sharing system. Thus at MIT, we could run our programs quickly on-line, fix errors immediately, and run them again as often as needed.  At the EDF, however, we were thrown back into the old batch processing environment, in which we punched our programs up on decks of Hollerith cards (often called "IBM cards"), like the one shown above. We submitted them, and depending on the backlog, we might get in one or two computer runs a day. I think that the program we wrote and debugged at EDF in the course of two months could probably have been completed at MIT in two weeks. The French work environment struck us as pretty laid back. We'd generally eat lunch in the company cafeteria. I recall that one day they offered the French dish "tête de cochon" (pig's head), and I tried it. Now, although I'll eat almost anything, I don't like corn. The French also eat almost anything - rabbit, frogs, snails, and so on, but historically, they also didn't eat corn, thinking it fit only for les vaches (the cows). So maybe I was born French, but in the wrong place. Except my advice to you is, stay away from tête de cochon. After lunch, our whole group generally walked off campus to a small local café. There, we played a French version of the card game "crazy eights". Ordinarily in that game, the person who gets the most points is the loser. However, as we played it, the cost of our coffees was split between the last player in the ranking (the player with the most points) and the middle player in the ranking. This meant that towards the end of the game, if a player risked finding himself in the middle, he might attempt to deliberately take on some additional points (it's easier to try to lose than to try to win). But sometimes a player was wildly successful at taking on points, overshot and ended up with the most points, and still had to pay for the coffee. It was a very clever and amusing exercise. Between the cafeteria and the café, lunch could run to two hours. On our last day at work, we were informed that it was traditional for the group to share a round of cognac with the departing stagiaires (trainees). But Larry was one of the losers in the card game that day, so he ended up paying half. That was when we found out that the cognac was the same price as the coffee - one franc (about 20 cents in those days). We could've had cognac every day for the same amount of money. Back at the Cité Universitaire where Larry and I lived, there were a number of cafeterias available. One of our favorites was in the Moroccan pavilion, La maison du Maroc. Having lunch there one day, we found ourselves in line behind a couple of young women who were speaking English. It was obvious that they were from Liverpool, because they sounded just like the Beatles. Ignoring all the other tables in the largely empty cafeteria, we sat down right next to them. They didn't initially seem too pleased by this. They later said that some of the Moroccans who lived in the pavilion had been annoying them. Since Larry and I both had black hair and spoke to them in French, they initially thought we might also be Moroccan. Of course, we eventually asked them where they were from. They replied that they were from Liverpool, which we already knew from hearing their distinctive accents in the cafeteria line. When asked in turn, we told them we were from Boston, Massachusetts, in the United States. At this point one of the women, Julia, said in English, "Well, why are we speaking French then?". We explained about our French immersion pact. I think Julia thought we were a little bit crazy, and besides, her friend didn't speak French, so we spoke English with them from that point on. Students get a lot of benefits in France. We had been given student discount certificates for various venues, which had included some Parisian cabarets (probably only in France would that be considered an educational benefit). We therefore proposed that they accompany us to one of these on a subsequent evening, and they accepted. Larry and Julia got along well, and she invited him to visit her in England after our stage was completed. After our return to the United States, he subsequently invited her to visit him here. Larry and I both returned from that summer with vastly improved French, but it turned out that Larry's most significant acquisition was a wife.

Note 1: Once in a Paris airport, the top line of a sign in a café read "THE NATURE". My English-speaking brain read it as English, and I mused aloud about what "the nature" might be. Someone nearby said, "That's 'thé nature' - plain tea." The sign was in French (duh! I was in a Paris airport). The lack of the accent mark on the E tripped me up, but it's usual in French to omit accent marks on capital letters. [return to text] Note 2: Named in honor of my aunt after her retirement, the Académie Musicale Internationale "Barbara Krakauer" was located in Vaison la Romaine, where Margie and I once visited it. [return to text] Note 3:

See for example my blog entries Véronique and Monsieur L'Oiseau. [return to text]

|

I went to France with my friend and MIT classmate Larry Beckreck. He's shown to the left six years later at my wedding, for which he was Best Man. Our 1964 summer jobs were arranged by an organization called "

I went to France with my friend and MIT classmate Larry Beckreck. He's shown to the left six years later at my wedding, for which he was Best Man. Our 1964 summer jobs were arranged by an organization called " We lived for a couple of weeks in Montparnasse. Larry prefers his eggs scrambled, but for our first breakfast, he had to eat the fried eggs which were the default style of the local café, because he didn't know the French word for "scrambled eggs" ("oeufs brouillés"). Then, once the students moved out for the summer, we were moved to the "Cité Universitaire" on the south side of Paris. You can see a picture of the impressive main entrance to the right. We were able to stay in student housing because we were in an educational "stage", and we were placed in the Maison des Industries Agricoles et Alimentaires. The "Cité Universitaire" was also convenient because the location of the research center in which we worked was also to the south of the city, and could be reached easily by bus.

We lived for a couple of weeks in Montparnasse. Larry prefers his eggs scrambled, but for our first breakfast, he had to eat the fried eggs which were the default style of the local café, because he didn't know the French word for "scrambled eggs" ("oeufs brouillés"). Then, once the students moved out for the summer, we were moved to the "Cité Universitaire" on the south side of Paris. You can see a picture of the impressive main entrance to the right. We were able to stay in student housing because we were in an educational "stage", and we were placed in the Maison des Industries Agricoles et Alimentaires. The "Cité Universitaire" was also convenient because the location of the research center in which we worked was also to the south of the city, and could be reached easily by bus.