I've long been a Francophile, in love with things French. And since my honeymoon at a Club Med in 1970, I've been particularly fond of the French independence day, also called Bastille Day, celebrated on the fourteenth of July. See my blog entry of one year ago entitled Allons enfants de la patrie, which was posted on Thursday, the fourteenth of July, 2011. This year, 2012, July 14 is on a Saturday, two days from now. Just as Americans refer to the American independence day as "the fourth of July", the French call their holiday "Le quatorze juillet".

At some point in the evening's festivities, we all sang the French national anthem, called La Marseillaise, whose lyrics I had printed and handed out. This was my first singing of La Marseillaise in a two-day period.

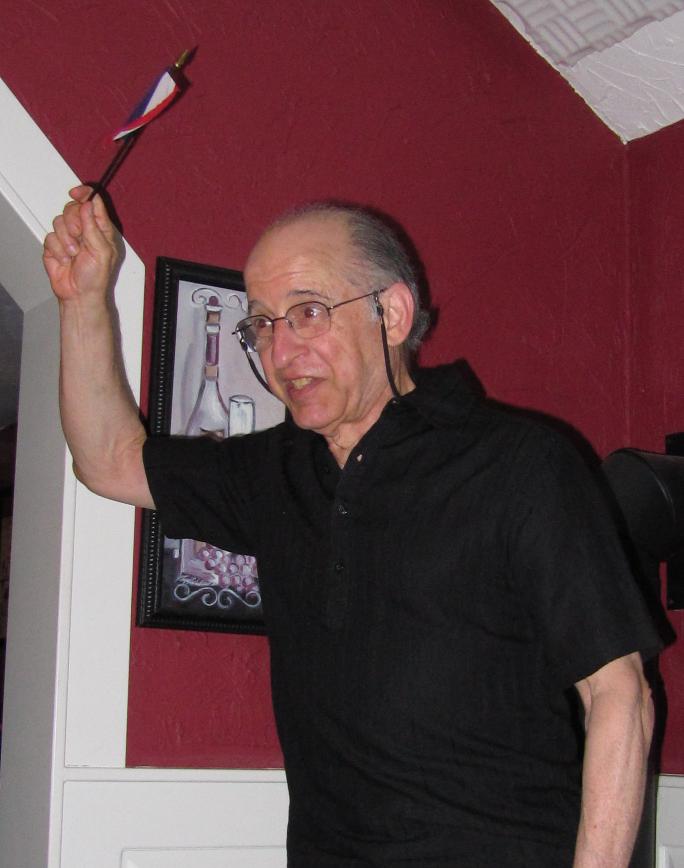

This was our fourth time attending this celebratory dinner, and my second singing of La Marseillaise this year. In only four years, it somehow seems to have become traditional for me to lead the singing at the French in Acton dinner. The picture to the right shows me doing just that, only a few hours ago, waving a French flag with great animation. You can click on the photo to see a larger version, then return here with your Browser's "Back" button. I'm not sure why I was selected to lead the singing. I don't even study with Cindy, Margie does. But when I asked, "Why me", Cindy replied, "Tradition". You can see a video here of Cindy introducing me, and just the first two lines of the song (you need to be able to view a Quicktime video). It was taken by one of our dinner companions, Paul Rowe. My comments in French are on the rather bloody nature of this national anthem. Below, allow me to translate La Marseillaise, with some comments, because the exercise casts some light on the difficulties of translation in general. First of all, when you translate a song, you need to give up on making the English lyrics fit the music, and you need to give up on making them rhyme. To translate a song to rhyme and fit the music is extremely difficult, usually impossible, and if you do it, the translation will not be very accurate. Here's my annotated translation of the anthem:

Fatherland? Sounds German. "Motherland" would be just as good. But "patrie" doesn't imply any particular gender (although of course, the word has a grammatical gender, like all French nouns). Maybe "homeland", but that lacks the patriotic connotations of "patrie". The fact is, there's really no exact English translation. And that's a problem that haunts all translations.

That's simple, if you know what a "standard" is. It's one of those vertical poles with a flag or insignia on top, carried into battle in the old days.

A different French version used the word farouche instead of féroce, "fierce" instead of "ferocious". A Frenchman I met once referred to someone as a "fou farouche", a marvelous expression meaning, sort of, a "raving madman".

Here's where the anthem starts getting bloody. "Significant others"?? OK, that's a little silly. But I'm trying to emphasize that there really is no exact translation of compagne. Despite its seeming similarity, it doesn't exactly mean just "companion", as one of my dictionaries says. That's a more general term, which doesn't imply lover or partner. Another dictionary says "consort", which is better, but which in American English sounds a bit archaic. The Wikipedia translation (as of today) finesses the issue by saying "women", assuming the soldiers are all male (certainly accurate for the time). That captures the idea, at least, that compagne is not referring to just any companion, but in fact to a significant companion, most commonly (but not necessarily) of the opposite sex.

Sillons here, "furrows", refer to the furrows of a cultivated field. In other words, the song is urging its listeners to spill so much blood that it could be used to water the fields. Note 1 Inspiring! Here, on YouTube, is a wonderful scene from the movie Casablanca, in which La Marseillaise is sung by those assembled in Rick's Café, interrupting a group of occupying German soldiers. A look of hatred is directed at the Germans as they sing, "... ces féroces soldats ... Ils viennent jusque dans vos bras". It gets the café shut down, of course - "I'm shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in here." That's the power of La Marseillaise.

Note 1: Whose blood is it? Regarding the reference to "sang impur" ("impure blood"), there are only two possibilities, the aristocrats who are being overthrown, and the revolutionaries (who wrote the song). When I first posted this blog entry, I assumed that if the revolutionaries referred to "impure blood", they must have been thinking of the blood of their enemies. So my sentence read, "... the song is urging its listeners to spill so much of the enemy's blood that it could be used to water the fields." However, it turns out that there is controversy about this. Whose blood is called "sang pur" ("pure blood")? It's aristocrats who are referred to that way (in English, they are "pure-bloods", or more likely "bluebloods"). With that interpretation, those with "sang impur" are the revolutionaries, and they are referring to the spilling of their own blood. Try Googling [marseillaise "sang impur"], and look for pages on the subject in either English or French. I came across this debate when I did some Googling to try to understand an entirely different issue: Why is the phrase "sang impur" sung without making the usual French "liaison". In a liaison, the final consonant of the first word, normally silent like most final consonants in French, is attached (modified) to the start of a following word that starts with a vowel sound. Thus "sang impur" should be pronounced sort of like "san kimpur", where the underlined an and im are nasal vowels, and the "k" sound is what becomes of the "g". But that's not the way the French usually sing it; they don't make the liaison, although I have no idea why. My French friends don't seem to know why either. You can hear it in the scene from Casablanca that I referenced above, or in my favorite rendition of La Marseillaise by Mireille Mathieu (with the lyrics below). This footnote added July 16, 2022, ten years after originally posting this blog entry. [return to text]  |

Yesterday, I hosted a potluck dinner to celebrate the holiday, and the cake shown to the left in the colors of the French flag, created by Norma Radoff, was one of the desserts served. The blue part of the cake is covered in blueberries, the white section is iced, and the red section is covered with strawberries.

Yesterday, I hosted a potluck dinner to celebrate the holiday, and the cake shown to the left in the colors of the French flag, created by Norma Radoff, was one of the desserts served. The blue part of the cake is covered in blueberries, the white section is iced, and the red section is covered with strawberries.