Like most engineers, I invent constantly. As mentioned in a previous blog entry, Patents, I have three United States patents, and a host of corresponding foreign patents. These were issued in connection with my work, and thus were assigned to my company, Kronos Incorporated. By the way, that blog entry also discusses patents that were issued to my father and his brothers, my grandfather, and my great-grandfather. But I also jot down on a list other potentially patentable ideas which I have from time to time. The list currently contains about 43 inventions, of which 19 would require a substantial amount of development to be brought to fruition. In addition, I have another 11 ideas that I've given the label "dubious". The collection is pretty eclectic, and only a few involve computers or electronics A couple of them have now been moved to a section of the document containing ideas that have been put on the market by others. This will invariably happen if one sits on an idea for any length of time. If I can think of something, then somebody else can. For four of my ideas, I actually wrote patent disclosures, signed them and had them witnessed, and stored them in my safe deposit box. This was back in the day when patents were awarded by the United States on the basis of "first-to-invent". The US has now switched to the system which I think was pioneered in Europe, "first-to-file". At the time I wrote these, a disclosure was sufficient to establish what was called an inventor's "priority date". Nowadays, an inventor is more likely to file a "Provisional Patent Application", rather than writing a disclosure. In either case, it's necessary to then develop the invention within a reasonable amount of time, a process which is called "reduction to practice". You may recall that I volunteer at MIT's Venture Mentoring Service ("VMS"), helping small companies get started. In 2007, I gave some thought to commercializing some of my own inventions. So I crossed the VMS line from mentor to mentee, calling my venture "Krakauer designs". I arranged for a VMS mentoring session, in which I discussed some of the ideas I found most promising with a team of mentors. While they found a few of my ideas to be intriguing, they emphasized that I needed to choose only one of them to get started (focus, focus, focus), and they gave me an assignment to further investigate the market for the idea I chose. The session also reminded me how much work it is to be an entrepreneur, something which I obviously should have known from my past history, but which I had rather suppressed in my enthusiasm. I ultimately decided that I really like being retired, and didn't want to put in the work necessary to turn any of my inventions into a product. I didn't make this decision very cleanly, but rather allowed a good deal of time to elapse without putting any work into the project. My thought of proceeding gradually faded. I'll describe here an idea that I considered developing initially. It was a product that I called a "Stable Table", and here's how I described it in my patent disclosure:

A three-legged table will never rock, because three points determine a plane. But even if the four feet of a chair or table fall on a plane, it may rock if the floor is uneven. Can something be done about this?

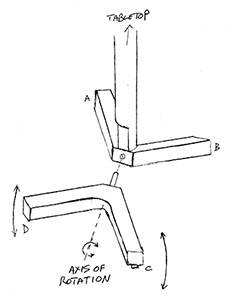

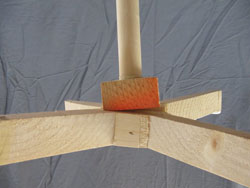

For a pedestal style table like the one shown at the top of this entry, one way to do this is shown to the right, in a figure taken from my patent disclosure. Effectively, the table has its two fixed feet (labeled A and B), plus a third virtual foot whose height is the average of the two pivoting feet C and D. It thus is essentially supported by three points, not four, and will not rock on an uneven floor. In developing this idea, I thought it worthwhile to build an actual table, to see if the idea would work as well in practice as in theory. Note 1 There was no need to build a full sized table, of course. I built the model shown in the picture just below. To give you an ideal of scale, the model's tabletop is 36 cm square (14 inches), and the table is 40 cm high (16 inches). Note in the picture that I've put a wooden shim under one of the feet, to show how the table behaves on an uneven surface. Below, the two pictures give a closer view of the pivoting mechanism, showing how the pivoted legs can rotate, within a limited range: In the interest of obtaining the broadest patent possible, my disclosure described the idea in quite general terms, in order to cover any mechanism linking two adjacent supports such that when one goes up, the other comes down. The pivot mechanism shown above, to be used on a pedestal type table, is only one embodiment of that general concept. The disclosure mentions some other possible embodiments, specifically for tables or chairs with four legs, as opposed to a central post. Two adjacent legs can be connected at their tops by a parallelogram linkage, for example. Alternatively, two small bellows or pistons filled with fluid can be connected by a tube. Click the next link to see the full patent disclosure that I wrote, which includes much more detail. It's eight pages long, including five pages of figures, presented as a PDF file. As I noted above, "If I can think of something, then somebody else can." So of course, before writing my disclosure, I did some searching on the web for what is called "prior art", meaning pre-existing patents or other forms of disclosure of the same idea. I didn't find any equivalent patents that seemed to predate my idea, although I did cite some related patents in the disclosure. However, after my VMS mentoring session, I received an e-mail message from one of the mentors, Jeff Bernstein. He had apparently done a better search than I, perhaps because he had used Google Patents, which I hadn't used. In any event, he came up with the following three pre-existing patents: US patent 5690303 A: Self-stabilizing base for a table

Although none of these patents completely covered the various different implementations that I had disclosed, between the three of them they pretty much covered everything. I concluded that if I were able to get any sort of patent on my idea, it would be fairly narrow in scope. Not being patentable is hardly fatal to a project, as patents (so-called "Intellectual Property", or "IP") are only one factor in a company's success in the marketplace. But the lack of patentability was one of the considerations that made me less inclined to go ahead with development of the Stable Table. In the end, I haven't felt motivated enough to put in all the work that would be necessary to develop one of my ideas.

Note 1:

As the well-known philosopher Lawrence Peter "Yogi" Berra once said, "In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not." I've cited this remark at least twice before, once in my entry Madhu and the death ray, and then again in my entry on Larry Black. But it always bears repeating. [return to text]

|