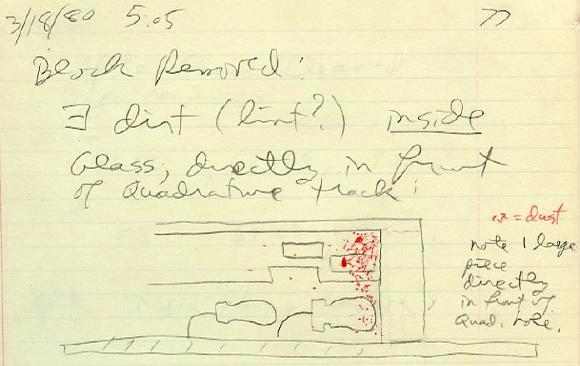

But in March of 1980, infrequently, timeclocks in the field would stop reading cards, and the service people would discover that the optics had gone out of calibration. They would simply recalibrate the optics, breaking the drop of enamel paint to allow them to turn the potentiometer "dial" (which actually looked like a slotted screw head). This put the clock back into operation, but left us no clue as to why the calibration had drifted in the first place. The distributor of our product was a New York City based company called, at the time, Interboro Timeclock (they had advised us during the design of the timeclock). I told Interboro that the next time a clock failed, they should ship it to me without recalibrating it or otherwise tampering with it. However, these were production clocks, being used by real customers, with a portion of their pay period data stored inside the clock. Recalibrate the clock, and it would begin working again, with the customer's data intact. Obviously, the customer had no desire to have the clock taken off the wall. Back then, we were selling all our clocks through Interboro, into their exclusive territory, which covered the whole northeast, including the Boston area. We could only give suggestions, not orders, to the Interboro service force. That's when we discovered, too late, that a new company should always have some local direct customers. Kronos didn't have a direct sales office until we opened one in Chicago years later, and even then, our direct customers were a thousand miles away. Finally one day, a clock failed very early in the pay period, with very little customer data in it. The customer was a printing company called "Panorama Press", and the Interboro service people (who of course also wanted to see this problem solved) convinced the customer that they would be better off with a brand-new clock. The failed clock, untouched, was express shipped to me. It arrived on March 17, in the evening, and I began working on it personally, keeping notes on everything I did in my engineering notebook. It had taken me a long time to have a clock sent to me in this state, and I didn't want to do anything that might cause a loss of information. So, I did not open the clock up right away. Leaving the cover on, I put it into maintenance mode, and did as much testing as I possibly could without disturbing the hardware. I next removed the front cover, and observed that the drop of the enamel paint on the potentiometer was still intact. I started doing additional testing, using electrical test points I could reach along the front edge of the printed circuit board that controlled the optics. I then decided to continue my work the next day, when I'd be more alert. The following morning, I pulled the optics board out on an extender, and made additional measurements, but there was still nothing out of the ordinary. Somewhere along the way, the company president, Mark Ain, came along and asked me how I was doing. I quickly realized that Mark was very impatient with my approach. Mark is the very essence of an entrepreneur; a hands-on guy with a bias towards action. He probably would have ripped the clock apart the instant it came in the door. In contrast, I'm a very careful engineer (some might say obsessive compulsive). I didn't want to do anything that might destroy evidence, but my methodical approach was clearly driving Mark crazy. There's a lesson here, which is why I'm spending so much time on this story. Mark is a person who understood that running a company successfully requires many different people with different personalities and different skills. Mark didn't hire me to be like him. Mark hired me to be a methodical engineer, who would dot the i's and cross the t's. And if you hire someone to do a job, and he's good at it, you've got to let him do it his way. And so Mark went away, I think because it was painful for him to watch me work so slowly. I spent the entire day systematically analyzing the clock's operation, concentrating on the electronics of the optics board. That was my main suspect, but I could find no problem with it. Thus it wasn't until the late afternoon when I removed the printer, exposing the optics reader block. This was an assembly that illuminated the timecard with "grain of rice" lightbulbs, and monitored the marks on the card with an array of phototransistor sensors. There were actually two phototransistors looking at the clock marks printed on the timecard, offset by a quarter of the mark spacing. These were called the "clock" and "quadrature" phototransistors, and having two of them allowed us to detect which way the card was moving at any moment, up or down. I pulled back these photo transistors, turned on the lights in the block, and put my eye to the holes in the block so that I could see what they were looking at. Moving a card up and down in the card slot, I could see the black marks of the clock track going by. But there was also a brilliant white spot of light in my view, in front of the quadrature transistor. It looked like a flash photo in which there's an object which is too close to the flash, and hence looks extremely bright and washed-out. What was it? I pulled out the optics block for a closer inspection. The bright light was caused by a piece of paper fiber that had been scraped off a timecard. It had gotten inside the block, under the protective glass, and lodged in a position which put it in view of the quadrature track photo transistor. The constant light reflecting off this piece of lint added a bias to the signal seen by the photo transistor, and that's what was responsible for altering the optics calibration. Although this discovery caused us to have to better seal the optics block, and to gradually replace every block that was already out in the field, the solution to the problem was now known. I still have my engineering notebook, so here's a portion of my notes from that day: Note 2  Later on at Kronos we consulted with a psychologist whom we called our "corporate shrink", who helped us work out personality conflicts between various members of the management. One of the conflicts we worked on was between me and Mark. Mark's bias for immediate action drove me nuts - it seemed like impulsiveness to me. My methodical approach drove Mark nuts, seeming to him to be overly obsessive. One day, our corporate shrink asked us both to write on a piece of paper how long it had taken us to make a particular important corporate decision (one which we had discussed with him earlier). He then read the pieces of paper, and revealed that each of us had written, "three days". I protested, "but Mark, as soon as we asked the question, you said we would definitely choose option A. You made a decision immediately." Mark replied, "but that's not what we did, is it?" It turned out, rather to my surprise, that Mark and I typically took about the same amount of time to make a decision. The difference between us was not in how much effort, data gathering, and analysis we each put into it. The difference instead was what we each said during the process. If asked, I'd say, "I'm still working on it." But at any given moment, Mark would express his current thinking with great certainty. Later he'd change his mind, often oscillating wildly over time between the alternatives. But it would still take him the same three days as it took me to settle upon a final answer. We found it easier to work together once we realized this. There are several morals to this story. Everyone knows that a company needs a mix of skills to be successful, but not everyone pays explicit attention to managing the mix of different personalities that come along with those different skills. Had Mark been as detail-oriented as I, he would not have been the excellent company president that he was. And had I had Mark's personality, I would have been a better manager, but not a very good engineer and troubleshooter. You can see another Kronos troubleshooting story in entry #0056, "The house of turkey death". Some day I'll post other such stories from Kronos and elsewhere, including one about trying to run our communications network in a Canadian manufacturing plant that shot artificial lightning bolts at its own product. Stay tuned. Working on your management relationships pays off. Although Mark and I had rocky moments, we worked productively together for almost 25 years.   Note 1: The word "clock" in "clock track" has nothing to do with the word "clock" in "timeclock". A "timeclock" is, among other things, an actual clock that keeps (and displays) the time of day. In electrical engineering jargon, a "clock track" is a signal that tells a circuit when to sample the value of another signal, usually called a "data track". The value of the data track is generally sampled upon a transition in the clock track signal. Most dictionaries don't recognize "timeclock" as a single word, preferring "time clock", and an internet search prefers "time clock" over "timeclock" more than ten to one. But Kronos found it to be a useful word. [return to text] Note 2: The backwards "E" on the third line is a common mathematical symbol meaning "there exists", which I sometimes use as a shorthand in my notes. [return to text]  |

One of my strengths as an engineer is that I've always been a good troubleshooter. In Entry #0005,

One of my strengths as an engineer is that I've always been a good troubleshooter. In Entry #0005,  Recall that the initial Kronos product was a microprocessor-controlled timeclock, shown to the left. Once a few timeclocks had been in the field for a little while, a new intermittent problem began to occur, although so infrequently that it had never occurred in any of our

testing.

Recall that the initial Kronos product was a microprocessor-controlled timeclock, shown to the left. Once a few timeclocks had been in the field for a little while, a new intermittent problem began to occur, although so infrequently that it had never occurred in any of our

testing.